American organisations are rolling back initiatives on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI). But, is this relevant to firms operating in other countries? Charlie Lin writes that despite this American rollback showing visible effects on EU and UK companies, this fluctuating landscape could be an opportunity for organisations everywhere to reflect on their EDI practices. His research shows the potential of Inclusive Leadership as a foundation for resilient, productive, and equitable workplaces.

The shifting landscape of inclusion

In the United States, directives from the Trump administration have led many organisations to roll back initiatives perceived to relate to Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI). This not only applies to government agencies, but also includes major companies like Google, Amazon, and more.

Yet this trend is not confined to the US. Despite the EU implementing a Pay Transparency Directive to address gender disparities, repercussions are already visible elsewhere, with GSK pausing UK diversity initiatives including mentoring for women and social mobility programmes.

Instead of reacting defensively, companies should use this fluctuating landscape as impetus to reflect on EDI practices, refocusing on the meaning and long-term value of inclusion. This helps ensure that benefits for organisations, and the people who comprise them, endure shifts in the sociopolitical climate.

A brief history of inclusion

Historically, organisations embraced EDI as a pragmatic measure in the war for talent to widen recruitment pools, avoid groupthink, and better reach diverse customer bases.

In recent decades, growing public awareness has led to increased pressure on organisations to take public stances on social issues such as feminism, environmental sustainability, and systemic racism.

When EDI falls short

However, many of these efforts devolved into performative company allyship by co-opting progressive movements through tokenistic initiatives, hollow statements, and insincere logo changes. Without embedding inclusion into systems of reward, accountability, and resource allocation, progress will remain superficial.

LSE Associate Professor Grace Lordan highlights that about 90% of Fortune 500 organisations have EDI initiatives, but they rarely translate into impactful change—they are predominately evaluated through short-term satisfaction surveys that show initiatives in a good light, rather than measuring long-term, systemic progress. EDI training often exemplifies this misalignment.

The costs of stigma

The expectation of being stereotyped at work, called stigma consciousness, can cause psychological harm to employees and undermine the financial health of organisations.

My LSE dissertation research found that, while not always the direct cause of turnover, it can negatively impact crucial mediators like job satisfaction and affective commitment (emotional attachment to the company).

Even without directly causing turnover, this reduction in satisfaction and commitment has tangible costs to the organisation–lower productivity, increased absenteeism, and increased risk of talent drain to external recruitment.

The role of Inclusive Leadership

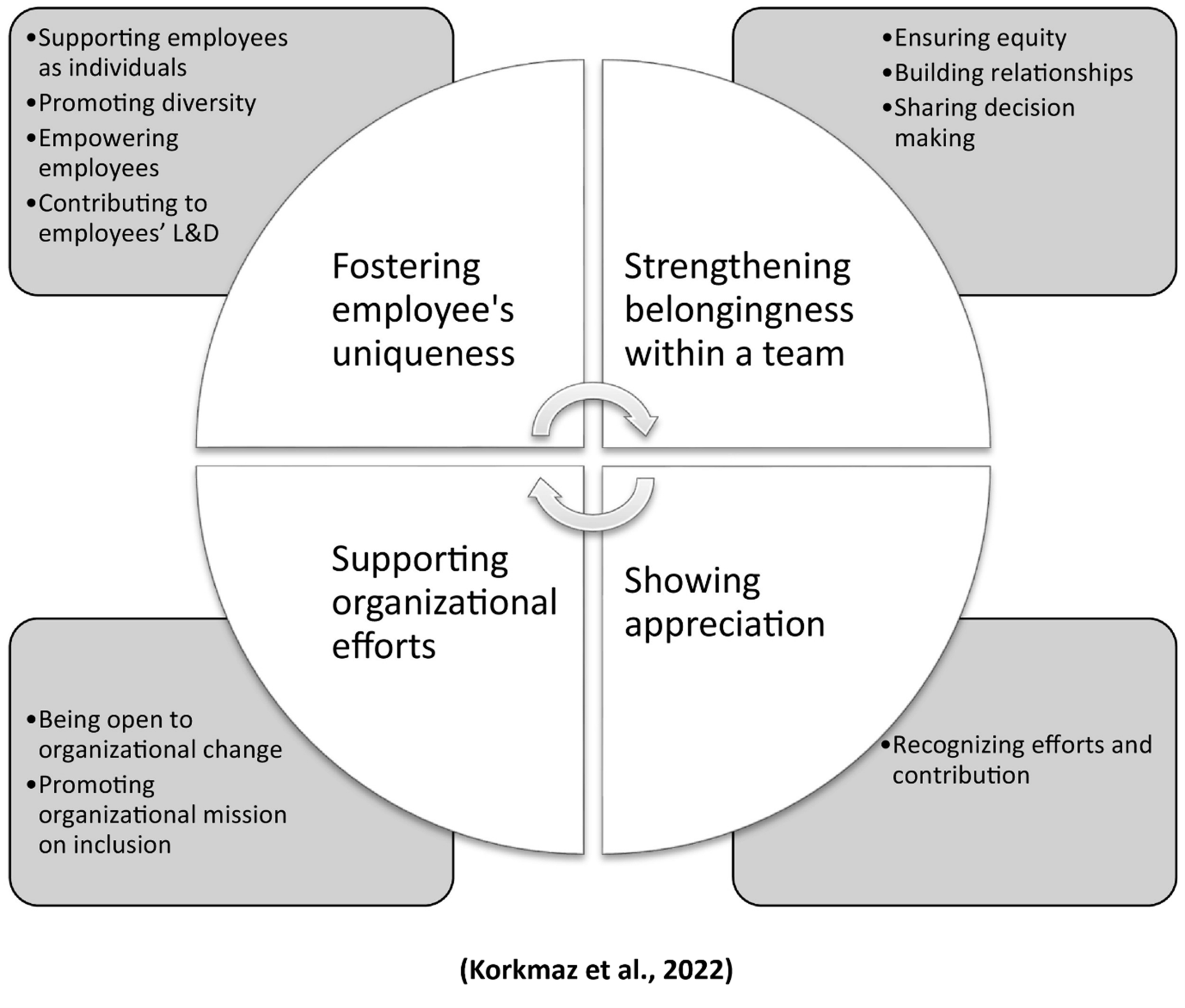

Inclusive leadership encompasses fostering individuality, strengthening belongingness, showing appreciation, and supporting organisational efforts.

My research demonstrated that this type of leadership can significantly mitigate the negative relationship between stigma consciousness and work outcomes. Additionally, it has a strong positive impact on innovation, talent retention, and work performance. In my research, I also incorporated further behaviours in my definition of inclusive leadership: being respectful, considerate to employees’ needs, seeking out different perspectives, and developing people’s talents to allow for advancement

Although the term ‘inclusive leadership’ typically has connotations of managerial behaviour, its principles can be applied across all levels: from individuals to organisations and society as a whole.

Putting Inclusion into Practice: Micro to Macro

Individual Level

1. Highlight others’ contributions

By giving credit to your colleagues in a public manner, particularly those who lack visibility with decision-makers, you help build a more accurate view of competency and more effective task allocation. Similarly, consider encouraging a competent colleague to share their insights more often in meetings, without putting them on the spot.

2. Team socialisation

Beyond ensuring that work socials are highly accessible (remote-friendly, minimal personal cost, and during work hours), the goal should be creating an environment that promotes exchanging ideas within and between teams, and that supports challenging assumptions constructively without fear of social penalties.

Activities that achieve this balance combine informal low-stakes interaction with shared learning. For example:

- Low-stakes sharing to develop common ground, such as sharing playlists or contributing to a work playlist as a team, hobby spotlights, and themed digital channels where people share pictures or comments around a topic of the week or month.

- Activities that flatten hierarchy remind us that new insights can be found from unexpected sources. For example, employee-led skill sharing on anything, from “using AI tools at work” to “baking for beginners”. Such activities can improve task-based trust (confidence in competence) and team-based trust (confidence in character), both essential to creating a psychologically safe and innovative environment.

Ultimately, true allyship is based on understanding the mechanisms of exclusion and power. To develop your understanding, practise systems thinking. For example, understanding historical policies (e.g. racially discriminatory housing policy and gendered labour laws) with contemporary business practices (e.g. algorithmic recruitment and gig economy models) reveals how these systems create and sustain the inequities in workplaces and society.

By asking who benefits and who is excluded, what underlying assumptions uphold the system, and how advantage or disadvantage is reproduced over time, it can be easier to spot where interventions and incentive redesign can be most effective.

Organisational level

Effective inclusion efforts should be complemented by implementing practices that reinforce inclusive behaviours and prevent bias.

Recruitment processes should include structured interviews, blind CV reviews, and selection panels that reflect the diversity of the organisation and its stakeholders.

Meeting procedures should have ‘no interruption’ rules, anonymous idea submission in advance, and rotating facilitation roles in meetings, to help reduce groupthink and encourage balanced participation. It is crucial that leaders model these behaviours to embed these norms, as research shows that the actions and words of leaders can account for up to 70% of an individual’s sense of inclusion.

Beyond static processes, we should implement effective feedback loops that gather practical insights to improve their efficacy. For example, managers should track measurable outcomes, such as:

- Retention rates across demographic groups.

- Perceptions of psychological safety and belonging.

- Representation across decision-making roles.

System level

Despite evolving public consciousness, the remnants of outdated perceptions of ‘professionalism’ and ‘leadership potential’ still linger in our systems. Today, the residual effects are obfuscated, with compensation and hiring decisions influenced by antiquated benchmarks that favour some groups over others and reinforced by the influence of informal professional networks and unequal distribution of opportunities and resources that distort participation and representation.

1. Closing policy loopholes

Reforms must account for the unintended consequences of introducing policies, particularly the loopholes that allow for their inconsistent application. For example, while the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act made it unlawful to deny promotion based on sex, such protections can be circumvented through informal decision-making. Implementing structured and transparent assessment panels not only reduces bias, but also strengthens trust in institutions and improves decision-making across the board.

2. Addressing structural imbalances

Inclusive behaviours at the micro level yield societal benefits, but they often rely on personal time, effort, and emotional labour. From a policy perspective, this represents a market failure: the costs are borne by individual workers and organisations, while many benefits (reduced discrimination, improved social mobility, higher welfare, and higher productivity) are spread across society.

To correct this imbalance, governments and organisational consortia should focus on mechanisms that spread the costs and ensure positive changes are rewarded, such as:

- Targeted funding mechanisms that reward demonstrated outcomes, e.g. matched grants or tax credits linked to measurable improvements in employment participation, workforce innovation, and productivity growth across demographics.

- Improved data and reporting standards that require transparent metrics on representation, pay equity, and advancement opportunities, allowing comparisons within and between organisations, enabling evidence-based policymaking and improved accountability.

- Cross-sector and intra-sector partnerships to scale successful inclusion interventions and reduce duplication of effort, e.g. the Management Consultancies Association

These levels are interconnected. Individual actions build cultures, organisational systems reinforce norms, and policy frameworks shape the incentives that sustain them.

Ultimately, instead of pausing initiatives under potential pressure, companies should reaffirm their commitment to inclusion as a foundation for resilient, productive, and equitable workplaces.

- This blog post represents the views of its author(s), not the position of the London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Management.

- Photo by Getty Images

The post Inclusion in organisations: roots and routes first appeared on LSE Management.