As a student at LSE, I am fortunate to be immersed in a world-renowned hub of learning, where ideas that shape the world are not only studied but actively debated – often by the very pioneers behind them. This vibrant intellectual community is one of LSE’s greatest strengths, and few experiences showcase it better than the School’s public events. These lectures bring together leading academics from LSE and beyond to share insights on global challenges and cutting-edge research.

On December 12, 2024, LSE’s Department of Management hosted a public lecture on automation, management and the future of work. Professors Erik Hurst, Chrisanthi Avgerou and Noam Yuchtman examined how automation and artificial intelligence (AI) are reshaping industries and the workforce, offering insights into the challenges and opportunities these technologies present.

Erik Hurst: The impact of automation on the labour market

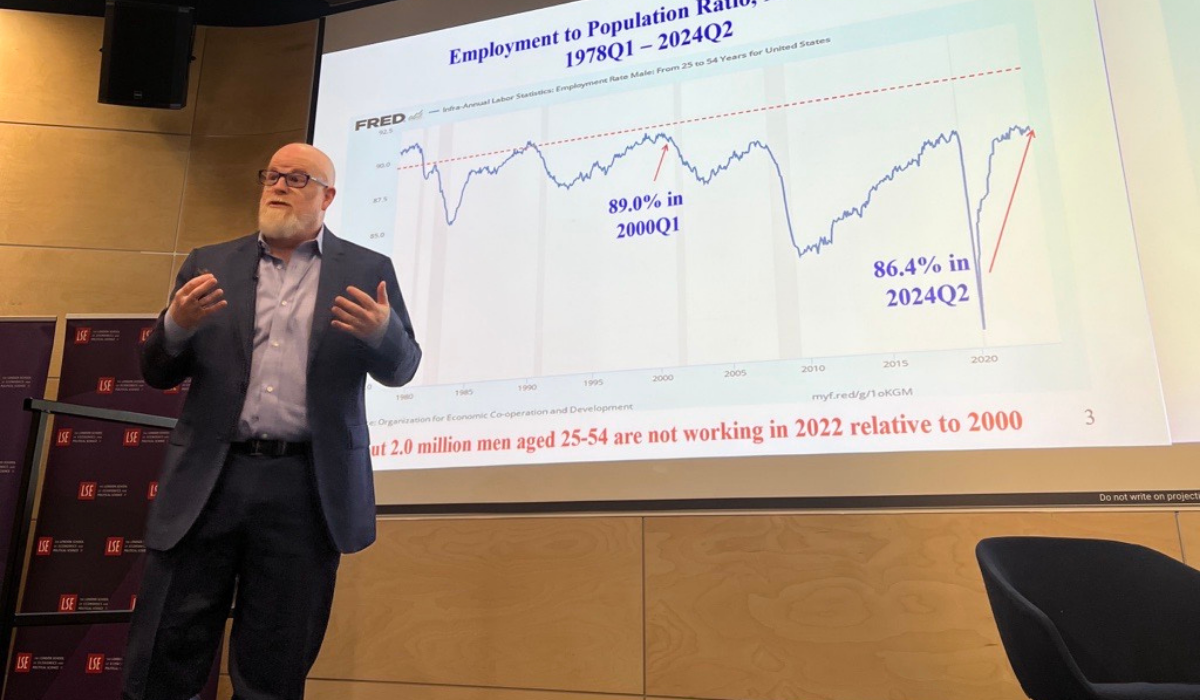

Hurst opened the discussion by examining the evolving employment landscape. He highlighted a concerning trend: the proportion of men without a bachelor’s degree who worked zero hours in the previous year rose from 8% in the mid-1980s to 14% today. Meanwhile, the employment-to-population ratio for women has stagnated at around 75% since the early 2000s.

He attributed much of this shift to automation and global trade, noting that 6 million U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost to automation between 2000 and 2010. Interestingly, sectors most exposed to trade with China also saw the highest rates of automation, illustrating the complex interplay between global trade and technological adoption.

To understand the labour market effects of automation, Hurst posed three critical questions:

- Is automation a complement or substitute for labour? For instance, computers complement R&D roles but replace line workers in manufacturing.

- Do displaced workers’ skills align with the demands of growing sectors? Unlike the smoother transition from agriculture to manufacturing in the early 20th century, today’s cognitive service roles require specialised skills that many displaced workers lack.

- Are there barriers to acquiring these new skills? Policy intervention is essential to help workers navigate transitions and mitigate skill mismatches.

“Technological unemployment isn’t a new phenomenon, but the scale of today’s skills gap requires urgent attention,” Hurst concluded.

Chrisanthi Avgerou: Technology’s socio-economic effects

Avgerou emphasised that the impact of technology depends not just on its design, but on how it is embedded within society – through management, policy and organisational restructuring.

She cautioned against the urgency often associated with new technologies, arguing that meaningful transformation takes time as organisations adapt. Modern technologies, she noted, operate within broader digital ecosystems, such as those seen in e-commerce.

While optimistic about younger generations’ ability to reskill, Avgerou highlighted challenges in the gig economy, where workers often lack long-term support and must bear the cost of reskilling themselves. She urged policymakers to focus on improving job quality and ensuring secure employment.

“I don’t expect much in terms of unemployment, but we do need policy and leadership to pay attention to the quality of jobs and the type of work available,” she remarked.

Noam Yuchtman: AI’s human boundaries and societal adjustments

Yuchtman explored the limitations of AI in replacing human labour, identifying three key areas:

- Empathy-intensive roles: Jobs like healthcare and caregiving require human touch that AI cannot replicate.

- Responsibility-intensive roles: Professions like judges or regulators demand accountability and oversight.

- Performance-intensive roles: In creative fields like music, art and athletics, we value human performance – even when AI can match or exceed it.

Yuchtman also addressed broader societal challenges, including shifts in wealth distribution and political tensions arising from labour market restructuring. While AI offers opportunities to augment human capabilities, he warned that without proper safeguards, it could exacerbate inequality.

Audience Q&A: Policies, inclusivity and education

One participant raised concerns about the wealth gap in creative industries, where independent workers often face the burden of upskilling without institutional support. In response, the panel underscored the importance of industry-driven lifelong learning initiatives, stronger representation and the role of unions – supported by effective policy – to promote equitable outcomes.

Another question focused on how policymakers could use AI to foster inclusivity. The speakers stressed the need for workforce retraining and regulatory frameworks to prevent wealth concentration. They noted that current AI applications are more about augmentation than substitution, offering a path towards more inclusive employment.

A final question on AI in education sparked optimism. The panel envisioned AI enriching classroom experiences by supporting teachers, not replacing them.

“Teaching is a relationship where human interaction remains paramount, and AI will complement that,” one speaker noted.

Key takeaways

- LSE’s ‘Automation, Management and the Future of Work’ public lecture highlighted the transformative power of automation and AI, while highlighting the complexities of their integration into society. From job displacement to education and inclusivity, the discussion stressed the need for thoughtful policies, organisational leadership and proactive reskilling initiatives.

- LSE’s commitment to fostering dialogue and exchanging ideas was evident throughout the event. As we navigate the future of work, events like these remind us of the importance of collaboration and innovation in shaping an equitable and sustainable workforce – and the role LSE’s community plays in realising that future.

The post Automation, management and the future of work: Insights from LSE’s Department of Management first appeared on LSE Management.